The wisdom of Aristotle, still going strong

By Dr Marcel de Roos, Psychologist PhD, the Netherlands.

By Dr Marcel de Roos, Psychologist PhD, the Netherlands.

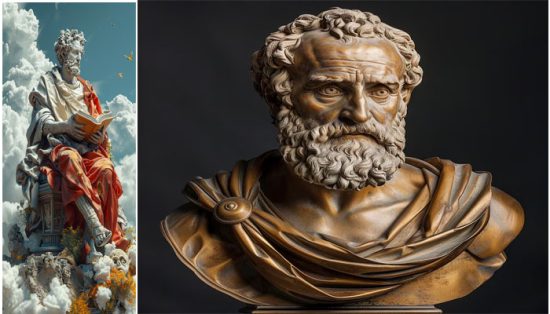

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE) can be considered as one of the founding fathers of modern psychology. He was a prolific writer, and he wrote about 200 lectures, of which only 31 survived.

He was a student of Plato (and he rejected his Theory of Forms) but was far more empirically focused and a strong advocate of accurate reasoning. Aristotle also thought that general principles can be important, but there are no strict rules because every situation is different. With each ethical dilemma, those involved need to be extensively immersed in the details of the particular situation.

Most contemporary books about happiness describe “objective happiness”, which can be measured by factors as having a good health, longevity, a loving family, and freedom from financial worries. But there is also “subjective happiness”, which has to do with satisfaction or feeling good about yourself. This kind of happiness can be described, but not measured. We can never fathom from outer appearances whether a person is truly happy or not: a seemingly cheerful person can be very depressed inside. And a relatively short life can be very satisfactory while a long and healthy life very disappointing.

Aristotle was the first philosopher who studied subjective happiness and he developed a program how to become a person with a happy and meaningful life. He propagated a life with active, practical, flexible, social, independent and “good” intentions. The state of mind that is the result of this, is “eudaimonia” (his notion of happiness).

In his Ethica Nicomachea he wrote that many people confuse certain forms of desirabilities like pleasure, wealth or fame, with the meaningful and commendable goals that he mentioned. The problem with the former is that they are strongly influenced by chance (see for example nonsense like “the law of attraction” or “manifesting”, where you can easily fall into a depression when the promised results fail to materialise, because life has its natural quirks and setbacks, and you start blaming yourself), while goals that incorporate social and community involvement can generate the kind of meaningfulness where “eudaimonia” refers to.

His complete manual for a meaningful life can be summarised in one sentence: choose for the golden mean, and in function of the circumstances. You can think for example of food and alcohol which we can consume more at a party than on an average day, but also of eroticism. The hypersexual male or female who jumps from one bed after the other and tries out every position, gender and gadget and who continually tries to excel by means of a cocktail of viagra and cocaine, finds his or her opposite in the frustrated ascetic who has denounced sex and as a consequence thinks of it the whole day. Likewise, courage is the middle between recklessness and cowardice, calmness between hotheadedness and valium-apathy, and each example always depends on the context.

Aristotle emphasised that maturity isn’t related to biological age: there are young people who are emotionally quite grown up and there are older people who will never reach full psychological and emotional growth. In addition, he believed that people who suppress their emotions too strong, are not capable to live a life where they can pursue effectively commendable and meaningful goals. In this sense he seems to be very modern and psycho-dynamic orientated.